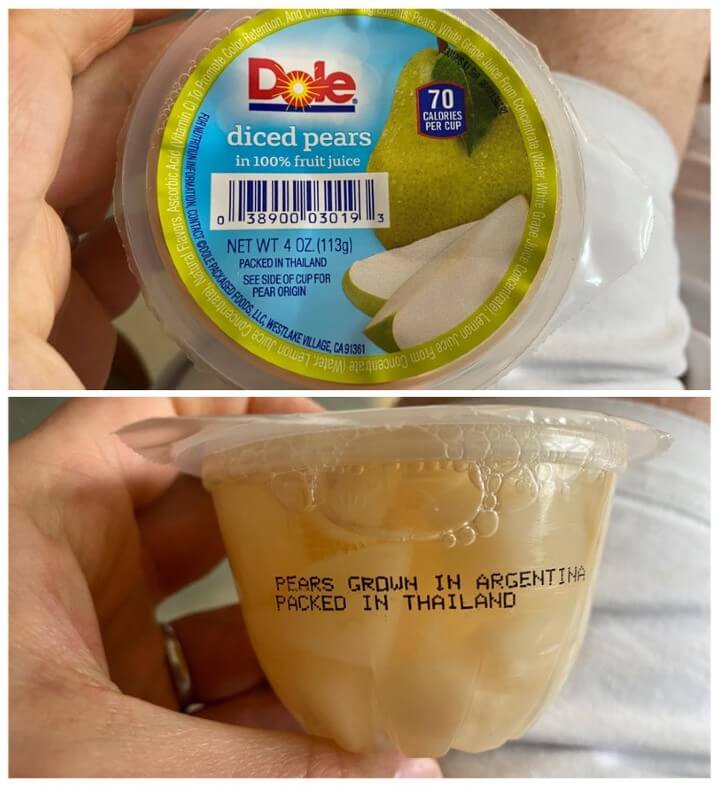

Earlier this week, a Reddit user made waves when they posted a picture of a package of Dole diced pears with the caption, “Argentina–> Thailand –> USA. These pears took two trips across the Pacific ocean before I ate them.”

The internet flipped its lid.

People like me weren’t remotely surprised. That’s because we’ve known for decades that the average meal travels over 1500 miles to get from the farm to your table.

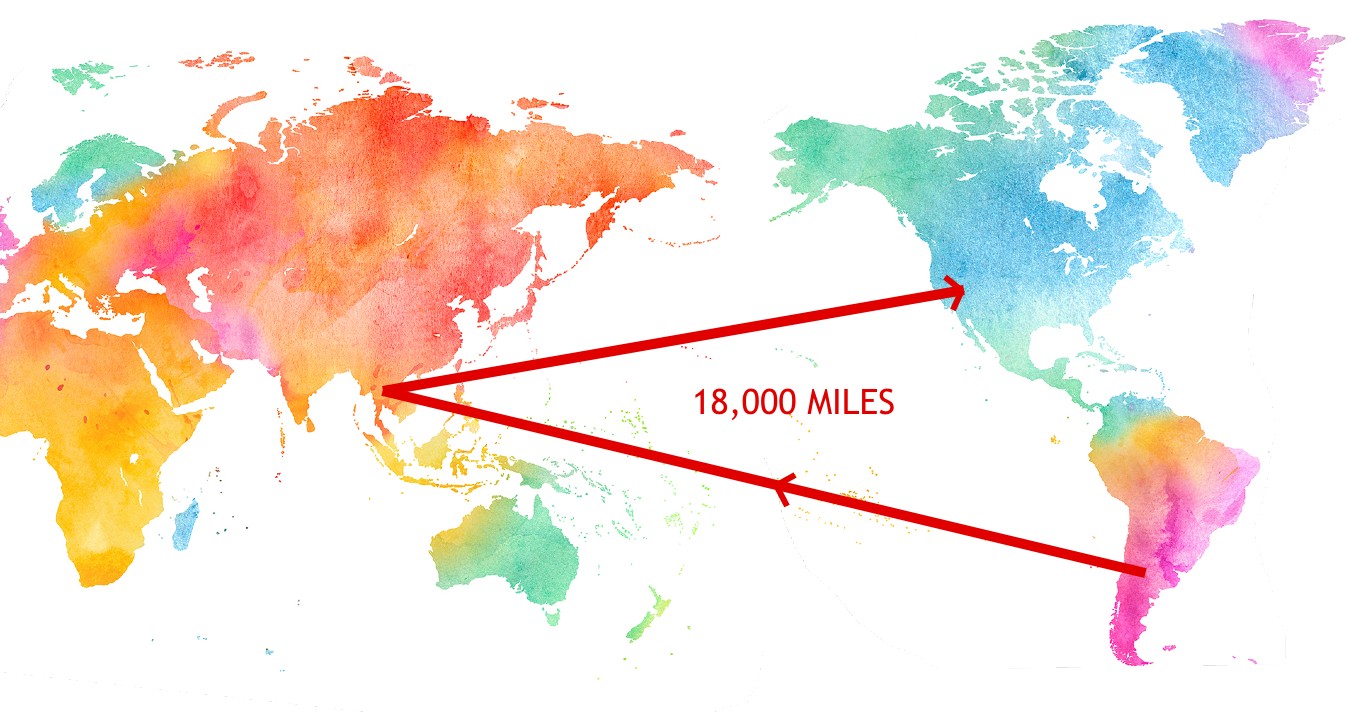

Granted, those pears traveled far more than 1500 miles. The distance from Argentina to Thailand is over 10,000 miles, and the distance from Thailand to the United States is another 8,000.

It is kind of mind blowing.

Nevertheless, it begs a number of questions.

First, when were those pears even picked?

I’ve reported before on the way modern food preservation science has extended the shelf life of fruit. Supermarket apples are usually at least a year old by the time they make it into your kitchen!

According to the Pear Handling Manual published by the USA Pears trade organization, the life of a pear in the US isn’t that much different than the life of an apple (or any other fruit or vegetable in the US, for that matter).

Pears are harvested before they’re fully ripe then stored in bins for 3-5 weeks before they’re sorted and packed. They’re then transported to a long-term storage refrigerated warehouse where they’re stored for up to 8 months in a expertly maintained environment that controls the exact temperature, humidity, and atmospheric make up of the air.

Before pears are ready to be sent to supermarket shelves, they’re “conditioned” by being slowly brought back from their state of hibernation as ethylene gas is added to their environment in increasing volumes and the temperature of the storage room is raised, which induces the ripening process.

Then, in the magic moment when the pears are measured to be just ripe enough, they get shipped out to stores.

So, to answer the question: the Dole pears that traveled across the Pacific ocean twice are, like most pears, probably anywhere from 6-10 months old.

Nutritionally, this is devastating news, as the majority of studies indicate that after just 7 days in refrigerated storage after harvest, fruits and vegetables can lose up to 77% of their vitamin C and the majority of their antioxidants (source, source 2).

Second, how is this economically possible?

We live in a crazy, crazy world in which it is somehow cheaper for food manufacturers to harvest pears in South America, ship them across the ocean to be processed and packaged, then ship them back across the ocean a second time to be sold in supermarkets than it is to source pears locally.

How do I know it’s cheaper? Because that’s what they’re doing, and their driving motivation as a US corporation is profit.

Why is it cheaper? That has to do with globalization.

Globalization is what it’s called when an industry starts operating on an international scale. The globalization of our food supply is why we can have Argentinian pears in February and Mexican tomatoes in January.

But it comes at a cost, namely to the people in developing nations who are providing all our labor for pennies. While these situations are moderately more ethical than slave labor, the effect is a loss of food sovereignty and rising poverty.

Vandana Shiva, arguably the world’s leading expert on the globalization of our food supply elaborates, describing how industry leaders use bad statistics to mislead the world about the negative impact of globalization:

I understand the concept of poverty as depriving people first and foremost of having a livelihood to provide for themselves; second, of being able to meet their basic needs with dignity, and third, of having the freedom related to an economic democracy. The absence of any of these conditions is poverty….

Why is this happening? First, it is because farmers are being displaced, because the globalization project is, at bottom, a land-grab project. If you lose your land to grow food [because a corporation bought it], you don’t have food. The second reason is that the entire agricultural fabric of India has been destroyed to make way for globalization. In the period from 1995 to today farmers’ incomes have dropped by 50 percent….

How is the alleged reduction in poverty manufactured? They stop measuring how people are living and start measuring how much more people are spending. If you had land, you were spending zero on food. Now you don’t have land and you’re working as a daily wage labourer—and you’re spending more on food! But spending more on food is an indicator of poverty. If I have a clean river next to me, I drink clean water. I don’t spend on water. Then the waters get polluted. Industry starts to dump. Expanding cities turn our rivers into sewers. Even the poor have to start paying for water—maybe not bottled water, but at least tanker water.

(source)

In the natural order of things, it is completely logical that food grown locally, with fewer costly chemical inputs, should be less expensive than food that had to be shipped halfway around the world and was grown with costly purchases of seeds, fertilizers, insecticides, and fungicides.

And yet, globalization has completely turned the natural order of things on its head. It’s given us access to non-local, out-of-season food grown with costly chemically-engineered inputs at a fraction of the cost.

CORRECTION: We’re not paying the cost. People in developing nations are.

Third, what even is the carbon footprint of this kind of eating?

According to research published by Poore and Nemecek in 2018, 26% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions come from industrialized food production (source).

Calculating the precise carbon footprint of these pears is practically impossible without more information.

Suffice it to say, there is no way that shipping pears 18,000 miles before driving them another 1,000+ miles on average isn’t environmentally costly.

Finally, is this normal?

Or is this just an extreme, weird, one-off example? Is it common to ship food to other countries for processing?

Sadly, this is not an unusual practice. Ever wondered how salmon in your grocery store can be labeled both “Alaskan” and “Product of China?” According the USDA, it’s not unusual for fish harvested in US waters to be processed and packaged in China before being shipped back to the US for sale in supermarkets (source).

Likewise, it’s not even all that unusual for “100% grass-fed beef” to be certified USDA Organic and have been processed here in the US, but to actually be from cows raised in Australia or Uruguay. A look at the labels is perfectly misleading; it’s only looking at the fine print on the back that you can discern a different country of origin (source).

What can you do?

As always, the best solution is to know your farmer and buy directly from them. Visit your local farmer’s markets, find local sustainable farms & ranches, talk to your neighbors and find out where they get the goods.

If that’s not possible, you can always check out the trustworthy, online suppliers found in my Shopping Guide.

Finally, begin militantly reading labels. Just because a food is “organic” or “natural” doesn’t mean it’s anywhere near local or inherently more fresh.

(read the original Reddit thread)

|

Don’t ya Know that these are special pears……deluxe imported pears!!!! Can’t ya tell by the tiny portion and the high price!!!! rotf lol

They even have “natural” flavors in them. Probably some weird stuff to make it taste like a pear again after the long trip.

It’s actually more efficient to do it this way.

A container ship would take 32 days to make that journey to Thailand then New York at 23mph. At 5500 gallons per day on a 10,000 container ship that’s 17.6 gallons per container for the entire journey. That’s probably more efficient than any other form of motorised transport. From 40 tonnes (one container) you could probably make 320,000 pots of pears (40,000kg of 100g with 20% wastage). That’s 0.24ml of fuel per pot. So basically it uses less fuel to get your pot there than you driving to the supermarket, even taking into account the other groceries you’re buying. Perhaps you can double or quadruple that fuel figure to take into account the truck shipping to the supermarket but 1ml of fuel is still less than it takes your engine to start.

Then you factor in that a load of pears might be going to central processing in Thailand but then being delivered globally alongside other products, shipping all to a central hub is more efficient that shipping half loads or quarter loads and doing small processing runs.

Spot on J F! thank you for your insight

Yet another lesson learned in 2020/2021. Don’t give up personal autonomy and liberty because of global dictates and mandates by those who would harm my family. We’ve kicked so many sources of tyranny to the curb and haven’t looked back.